CONSERVE. PLAN. GROW.®

It’s a Mixed-up Investment World!

April 18, 2016

Source: Strategas

The most successful investment theme in 2015 centered on investing in high growth stocks like Alphabet (formerly Google), Amazon, Facebook and Netflix. In a slow growth economy, investors placed a premium on companies that could deliver high revenue growth. Thus far in 2016, by contrast, we have seen many slower growing—but good dividend-paying stocks—lead the market averages. This re-direction of investment capital within the stock market can likely trace its origins to activity in the

bond market.

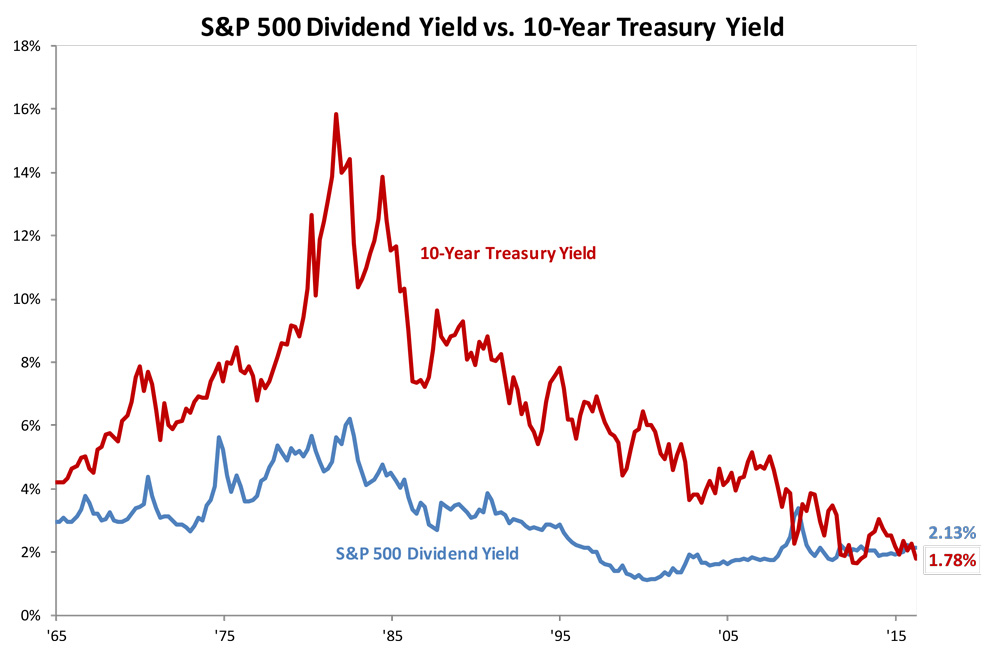

In mid-December 2015, the Federal Reserve raised interest rates and indicated that there would be multiple interest rate increases during the course of 2016. The Federal Reserve created an expectation that interest rates would rise throughout calendar year 2016. The US Treasury 10 year bond was yielding about 2.25% at the start of the year. In relatively short order, the yield declined to the 1.70% level. The bond market completely disregarded the commentary emanating from the Fed. Bond investors looking for a decent income return on their bond holdings have been challenged in this environment.

With expected future returns at such modest levels for bonds, investors have gravitated to more volatile investments like stocks in order to generate cash flow. There are plenty of stocks that yield 2-4% that have had a long track record of consistently paying dividends. These companies are in stable businesses and should be able to maintain their payouts even in the face of a low-growth economy. Traditional dividend payers like utilities and telecom companies are up over 10% this year as a result of investor demand. Investors have accepted the higher price-volatility of stocks in order to receive better cash flow from their portfolio. In effect, investors have been searching for stocks that act somewhat like bonds.

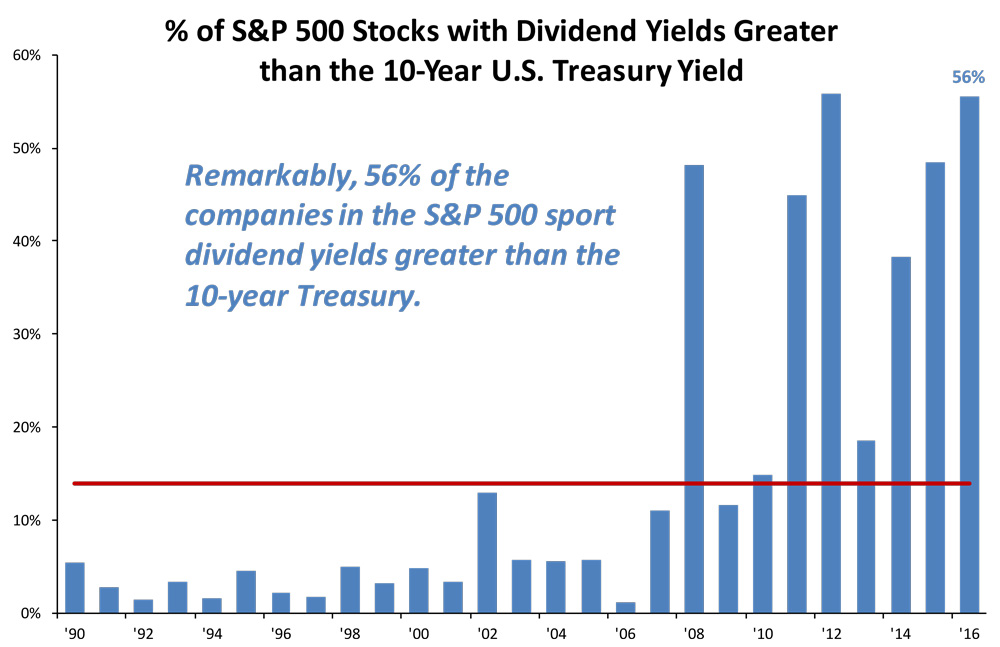

Historically, investors have purchased bonds for income, and stocks for capital appreciation. With the decline in interest rates, the values of bonds have risen appreciably. We now find ourselves in a strange world in which bond investors have been reaping gains on the appreciation of their bond holdings, while stock investors are receiving higher income returns on their stock holdings than on their bond holdings. Surprisingly, more than half of the S&P 500 stocks have dividend yields higher than the 10 year US Treasury bond.

Source: Strategas

Part of the reason that dividend paying stocks have been in demand is that investors appear less confident that the Federal Reserve will be able to implement multiple rate increases during the course of the year. Investors are also witnessing negative interest rates around the world, including in major countries like Germany, Sweden and Japan. Negative rates are a rather unusual phenomenon in which the lender ends up paying the borrower. “What better value enhancer for dividend yielders than the threat of the fixed-income market going to negative yields?” said James Paulsen, chief investment officer at Wells Capital Management.

At the same time as we have seen investors gravitate towards income-oriented equities, we have also seen bond investors return to the high yield bond market. High yielding bonds offer higher yields than bonds issued by creditworthy borrowers because high-yield issuers have lower credit ratings and thus are more vulnerable to default in a struggling economic climate. This category of bonds behaves somewhat like stocks due to their volatility and higher risk/return profiles.

Recently, I was working on a financial plan for one of our clients. The sophisticated financial planning software that we utilize is one of the most widely used platforms in the industry. The platform relies on investment return assumptions based on data going back to 1970. For purposes of retirement planning, the software default setting assumes that cash will earn 3%, short-term bonds will yield 3.5%, and large cap value stocks will generate 8% annually.

While these are probably reliable metrics for planning for 10-15 years into the future, the current yields on fixed income investments are well short of these assumptions. With cash currently earning not much more than 0% and short-term bonds yielding substantially less than 2%, it is presently hard to imagine that these are indeed realistic assumptions for these asset classes over the coming 10 years. At some point, we will probably see assets yield closer to their long-term averages, but in the meantime, investors are faced with accepting lower cash yields from their fixed income investments.

Investors appear to be substituting high quality dividend paying stocks for a portion of their fixed income allocation, and layering in more high-yield exposure to their bond allocation. Investors have to take on more stock price-volatility in exchange for this enhanced income from dividend payers, and more credit and price volatility risk with high-yield bonds. If the Federal Reserve does end up increasing rates over the next year or so, bonds may again provide reasonable cash flow for income oriented investors. In the meantime, looking to equities for income and to bonds for capital appreciation has become a familiar—albeit historically uncommon—characteristic of today’s investment portfolios.