CONSERVE. PLAN. GROW.®

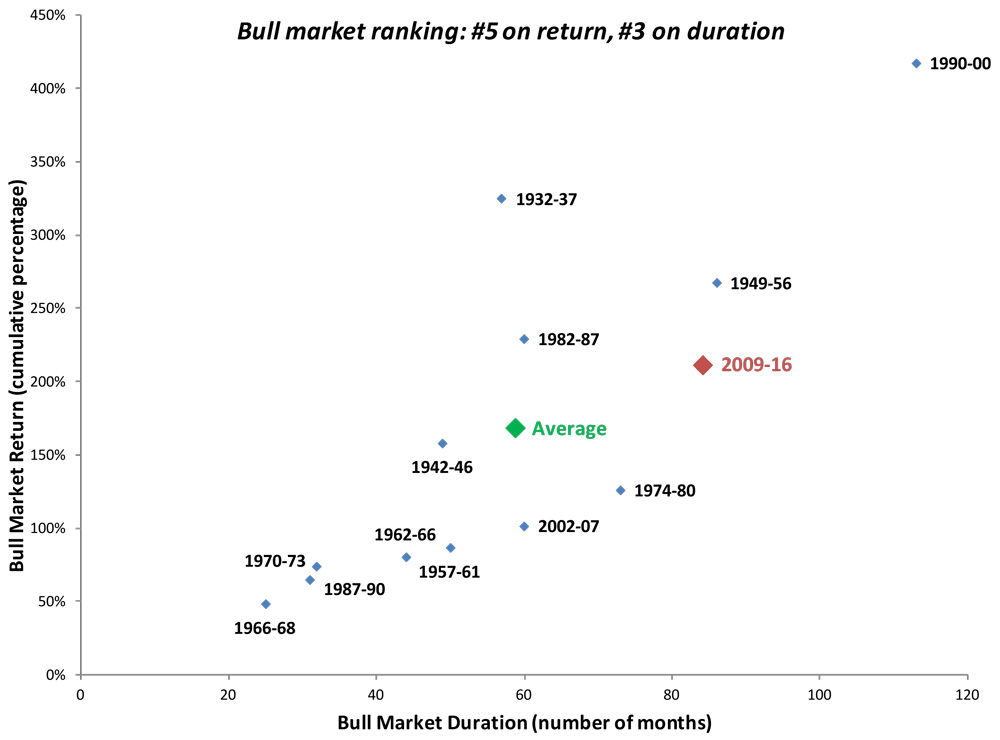

The sideways market of 2015 became even more indecisive in the first quarter of 2016. The S&P 500 Index stumbled out of the gates, and was down more than 10% by early February. In the ensuing weeks, the Index made a strong turn higher, ending the first quarter up marginally. At quarter end, the Index traded a few percentage points below its all-time high. Despite the volatility, the current bull market just reached its seven year anniversary in early March, making it the third longest and fifth highest returning run since the Great Depression.

Many market participants found great discomfort in the declines of January and early February. The idea that markets could swing so violently without explanation was insufficient, as investors have become accustomed to ready and plausible answers from market pundits. Of course, the easy answers are seldom meaningful and instructive. Amid the uncertainty of early February, an article from the Wall Street Journal titled “What’s Going On in the Markets?” (WSJ, 02/10/2016) captures the inherent difficulty of explaining short-term market movements:

“As investors and analysts search for reasons for the global volatility, what seems plausible one day is quickly disqualified when the market veers in the other direction… Finding a widely accepted, overarching thesis has proved elusive, leading to the rise of multiple, competing, largely unsatisfactory explanations. Yet analysts and traders keep searching, hoping to devise a road map for the peaks and valleys that lie ahead.”

Source: TFG, Strategas

The reality is that a road map for the peaks and valleys that lie ahead does not exist. Importantly, focusing on the short-term peaks and valleys diverts one’s attention from making intelligent long-term decisions. It’s difficult to remain attuned to your investment goals when you’re constantly inundated with noise. We believe that the analysts and traders attempting to bridge this divide will ultimately be unsuccessful. In the long run, market timing is a fool’s errand.

The corollary of that argument is that the near future is unknowable. The only way we know to intelligently account for this factor is to think long term. Benjamin Graham, the father of value investing, put it best: “In the short-run, the market is a voting machine – reflecting a voter-registration test that requires only money, not intelligence or emotional stability – but in the long-run, the market is a weighing machine.”

In a declining market, it’s easy to lose your bearings and get caught up in the short-term commotion. Staying level-headed in the short-run, during bouts of market volatility, is easier said than done. We would argue this has become tougher as market participants have become increasingly short-sighted.

In our view, financial markets have been influenced over the past two decades by a proliferation of products and investment vehicles that, in combination with financial incentives, have reinforced an increasingly myopic focus for many industry participants, including executives at publicly-traded companies, Wall Street analysts, and fund managers.

Publicly-traded companies face intense pressure to meet short-term financial targets. For corporate executives, beating or missing consensus earnings estimates can be the difference between a multi-million dollar bonus and looking for a new job. This pressure has a meaningful impact on behavior: in a study of 400 financial executives, researchers found that a majority of managers would avoid starting a project that would generate meaningful long-term value for owners if it meant falling short of the consensus earnings estimate for the current quarter (“The Economic Implications of Corporate Financial Reporting,” National Bureau of Economic Research, June 2004).

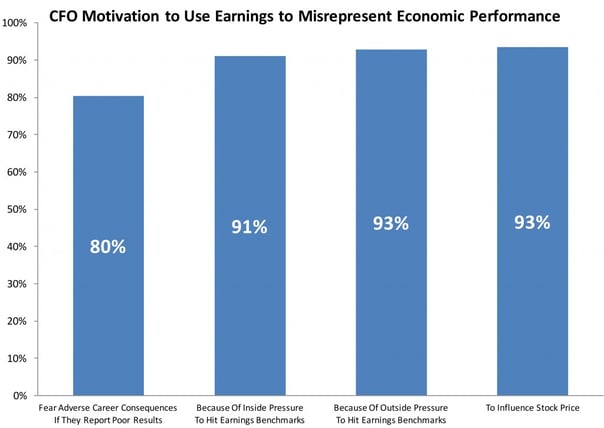

Source: Financial Analysts Journal

A recent CFO survey (“The Misrepresentation of Earnings,” Financial Analysts Journal, February 2016) suggests forgone investments are not the only path to beating earnings estimates: the participants estimated that in a given year, one in five companies intentionally misrepresent earnings by using the discretion available within generally accepted accounting principles. They estimated that the average magnitude of misrepresentation was ten cents for every dollar of earnings. To put that number in perspective, stock prices can move materially based on financial results (earnings per share or EPS) that miss or beat consensus estimates by a small percentage.

For the long-term investor, the reality is that quarterly earnings have a limited impact on the intrinsic value of a business. Much like market commentary and volatility, reported earnings in any given quarter are essentially noise. The headline figures are less important than what truly matters – sound capital allocation, building and sustaining competitive advantages, and maintaining balance sheet strength. As Albert Einstein once said, “Not everything that can be counted counts and not everything that counts can be counted.”

Recent innovation in exchange traded funds, or ETF’s, highlights how product development has encouraged the short-term investor mindset. Early on, ETF’s were primarily index funds, which provided broad market exposure in a cost-effective structure. It’s important to recognize that indexing can be a useful tool in meeting long-term financial goals, but it’s not a panacea. As many individuals found out during the financial crisis of 2008, it’s not any easier to stick with an index ETF strategy after the market has fallen 50% than it is to stick with an individual company after a similar decline. While ETF’s can be used to construct portfolios and meet client needs, it’s important to recognize that these “solutions” are not a magic bullet.

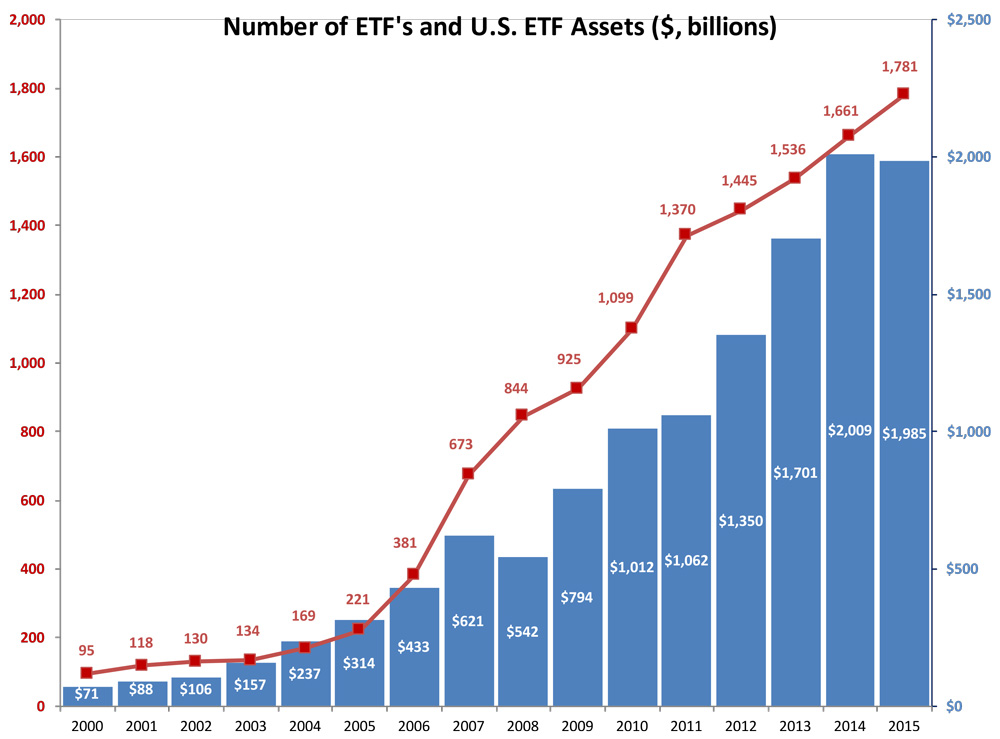

Over time, the industry has expanded beyond traditional index funds, and this is where we find fault. In the past 15 years, the ETF business has grown rapidly, from 100 ETF’s with $70 billion in total assets to 1,800 ETF’s with $2 trillion in assets. The rapid expansion of new alternatives reflects an industry capitalizing on the marketability of ETF’s in general. It’s not clear whether many of the new variations, like leveraged ETF’s, have the best interest of investors in mind. As opposed to offering long-term market exposure in a cost-effective structure, recently introduced products offer an avenue for participants to easily speculate on short-term market movements. They may serve a purpose for the people selling them, but it’s less clear that they add value for the individuals using them. When we read about these exotic ETF’s, we’re reminded of a story Charlie Munger tells about a friend who sells fishing tackle: “I asked him, ‘My God, they’re purple and green. Do fish really take these lures?’ And he said, ‘Mister, I don’t sell to fish.’”

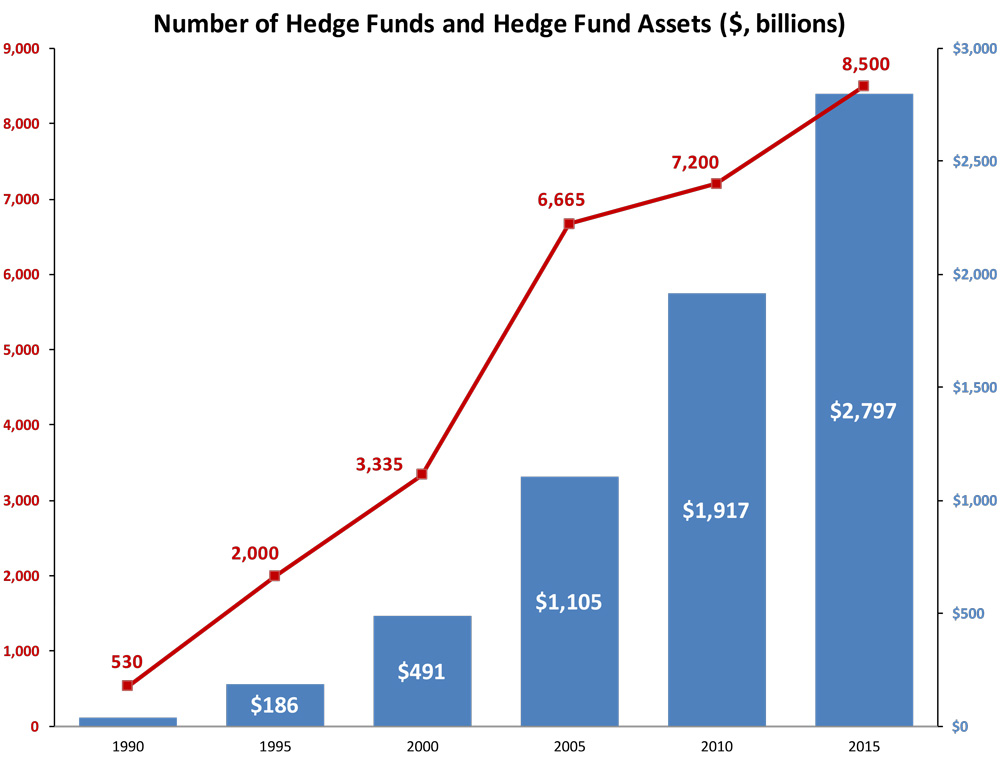

Similar to ETF’s, hedge funds have reported sizable asset growth over time. The industry has been the beneficiary of incessant investor interest, appealing to their desire to mitigate downside risk while generating absolute returns. In the early days, there were relatively few hedge funds managing fairly modest sums and returns were outsized. Their success resulted in more investors seeking out star managers. The compensation structure, referred to in hedge fund speak as “2 and 20,” which consists of an annual management fee equal to 2% of assets under management (AUM) and a performance fee equal to 20% of the fund’s profits, encouraged the proliferation of new hedge funds, an expansion in the number of strategies, and unbridled growth in assets. In addition, the rapid expansion resulted in intense competition between managers and an acute focus on generating short-term results.

Source: BlackRock

The focus on short-term results, in combination with greater influence from the hedge fund community, has exacerbated the market’s volatility and added additional pressure on corporate executives to meet short-term earnings targets. By way of example, activist hedge funds (similar to corporate raiders of yore) that agitate for rapid changes and instant gratification have tripled their AUM in the past five years.

As one might have predicted, relative performance by hedge funds as a group has begun to lag. Over the past three, five, and ten year periods, a simple blend of index funds (60% stocks / 40% bonds) has outperformed the Barclay Hedge Fund Index (“As Hedge Funds Returns Falter, Money Continues to Flow In,” NYT, 02/26/2015). As a result of poor relative performance, large investors like pension funds and university endowments are questioning their allocations and fees paid to hedge funds.

Source: CAIA Association

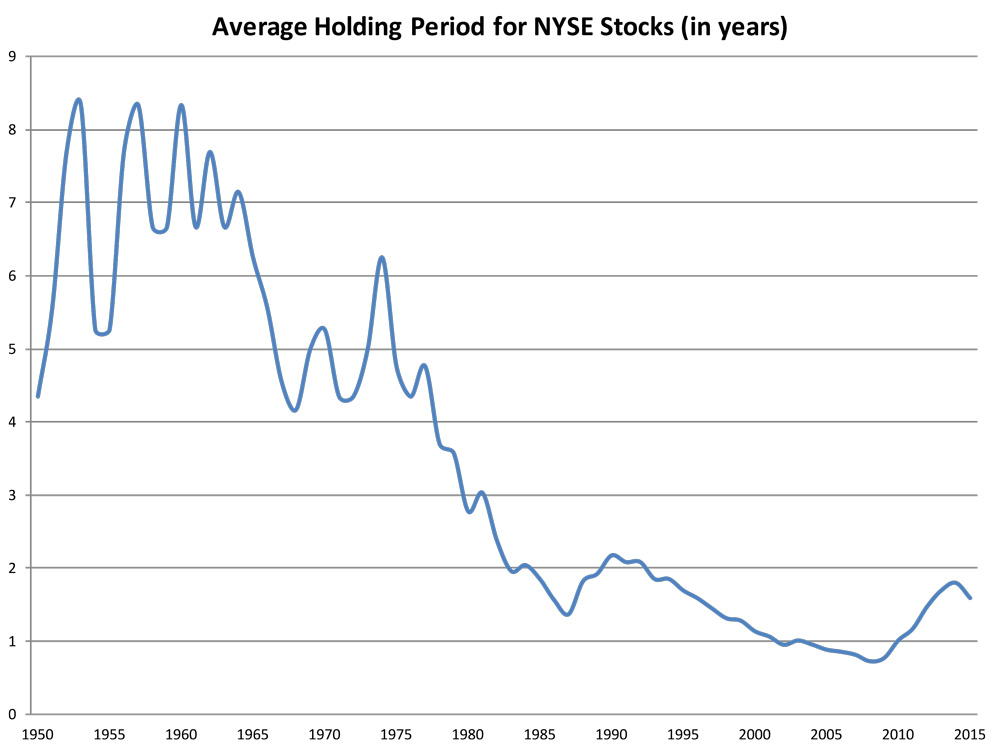

As other market participants shorten their time horizon, we believe opportunities arise for long-term investors. For us, that means it’s more important to focus on the long-term growth of the business, not fluctuating stock prices or short-term results. Based on the data, it’s safe to say most market participants are not long-term investors: fifty years ago, the average holding period for a stock in the United States was seven years; in 2015, it was nineteen months (with the average for the 100 largest stocks under one year). With the help of technology, individuals who have a casino mentality can speculate cheaply and quickly. In the long run, the odds of success are not in their favor.

A willingness to accept market swings with equanimity is critical to long-term investment success. Volatility tests conviction, but this is ultimately a good thing as it helps investors focus on properly aligning their investment objectives with their time horizon and risk tolerance. Importantly, lower prices present us with opportunity. Expected future returns increase as current market prices decline.

The primary issue investors struggle with – maintaining a long-term focus during tough market environments – remains. No matter how products and investment vehicles evolve, this will not change.

Source: TFG, NYSE