CONSERVE. PLAN. GROW.®

Have we seen the beginning of the Great Rotation?

January 16, 2017

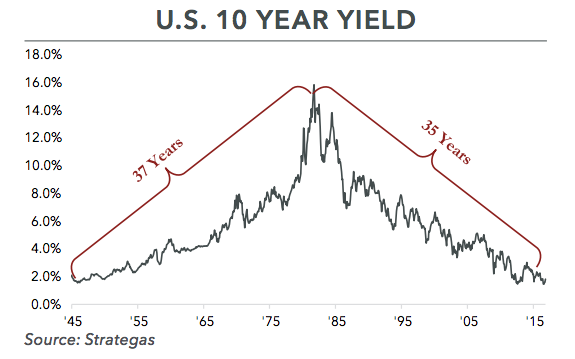

Over the past 35 years, interest rates on bonds have been in a gradual decline. The decline in interest rates has gone hand-in-hand with rising bond valuations since bond values move inversely to interest rates. Bond investors have thus enjoyed a long period of rising returns due to market appreciation in addition to the interest earned on the bonds.

During the last two months of 2016, we witnessed a swift and steep increase in interest rates. Whether we are now at the beginning of a long run of rising interest rates (and lower bond values), only time will tell. But if this is the beginning of a period of rising rates, we might also be seeing the beginning of investor preference for stocks over bonds.

Following the dramatic stock market declines in 2008-2009, many investors suffered significant losses in their investment portfolios. In response, many of these investors revised their investment allocation to focus on purchasing bonds rather than stocks. As interest rates declined in the wake of the Great Recession, bond values appreciated, giving investors twin benefits of reliable cash flow and improving valuations.

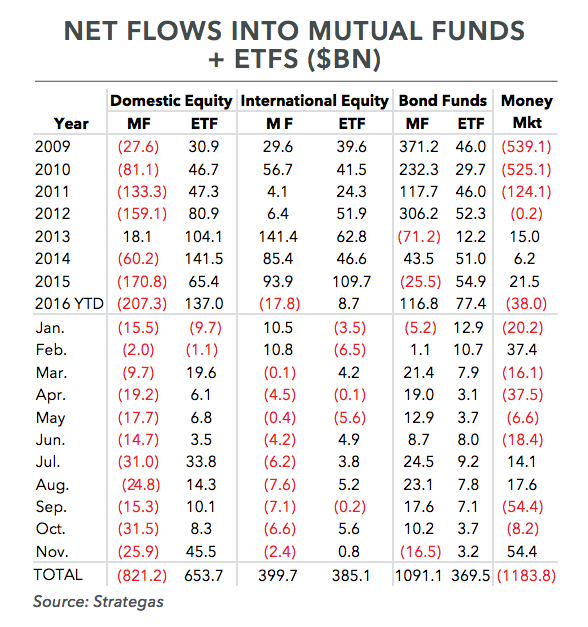

The table on the following page illustrates the flow of investment dollars into and out of Mutual Funds and Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs). As the table indicates, there have been net redemptions from domestic equity mutual funds and ETFs during a sustained bull market that began in 2009. The only year in which there were net inflows into equity funds was 2013, when most bond investments produced modest negative returns.

If we assume that most investors who invest in mutual funds and ETFs are individual investors (as opposed to institutional investors), we can assume that many of those individual investors missed the powerful stock market returns of the past seven years. Those individual investors were content to accept low but stable returns offered by bonds because they likely did not want to endure another nearly 50% decline in the value of their stock portfolio. Now, with the recent decline in bond values, those same individual investors may be rethinking their preference for bonds.

Individual investors have been highly skeptical of the equity markets despite strong returns since 2009. Perhaps their skepticism was justified, as underlying economic growth has been sluggish. Central bank intervention and periodic global shocks have also kept investors defensive. Thus, it is possible that individual investors may, as a whole, be over-allocated to bonds and underweight stocks.

While bond values have recently been declining, equity valuations have been surging. An incredible amount of money has flowed into stocks during the last two months of the year. As Michael Santoli was quoted on CNBC: “Bank of America Merrill Lynch calculated that the first week following Donald Trump’s election saw the largest rush into equity funds in two years, the biggest withdrawals from fixed-income funds since the early 2013 ’taper tantrum‘ in bonds, and the widest spread between stock and bond flows on record.” Bloomberg has calculated that in the month after the election, the global market value of equities jumped by $2 trillion, about the same size as the loss in the Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Index of bonds.

The significant rise of money flowing into stocks likely has investors who are overweight bonds concerned that they may be missing out on a massive rally. Fear of not participating in a growth opportunity can create an atmosphere of urgency for investors. In any event, the rapid pace of money moving quickly into stocks likely caught many investors by surprise.

It is not just individuals who who have favored bonds over stocks. Endowments have been gradually reducing their allocation to stocks for the past 15 years. In 2002, endowments had 50% of their assets invested in publicly-traded equities. This year, the figure is closer to 35%. While they were reducing their equity allocation, they were increasing their allocation to alternative investments like hedge funds and private equity. The alternatives have recently been underperforming relative to many equity indices.

Investors may now be at the forefront of a “great rotation,” a phrase first used by Bank of America in 2011, to describe the transition from investor preference for bonds to a preference for stocks. While it did not happen in 2011 when the phrase was first coined, there are several reasons why the rotation may be underway this time. With a strong employment environment and signs of stronger economic growth ahead, inflation expectations are rising. The Federal Reserve increased rates during December and indicated that they will likely do so again several times during the course of 2017. The incoming administration has given indications that they will favor fiscal expansion. Increased government spending implies higher borrowing, which could be another source of inflationary pressure.

Signs that the so-called Great Rotation is underway will be evidenced by a continuation of investors offloading bonds on a large scale. “We know in general that a lot of capital has gone into fixed income, so how investors react to this sell-off is really important,” said Michael Metcalfe, head of macro strategy at State Street Global Markets. “If they capitulate, they will drive the next leg of it clearly.”

Since the end of the last recession, hundreds of billions of dollars have been withdrawn from the equity markets and many more hundreds of billions of dollars have been invested in bonds. Because of the recent decline in bond values and the corresponding rise in stock values, we may see even more dollars committed to stocks than bonds in the future. Perhaps a supposedly “hated” bull market is now gaining favor among smaller investors. If so, this rotation into equities may become self-reinforcing, as the positive performance of stocks will entice more cash to equities.

With that said, it’s important to make the distinction between short-term market movements and long-term corporate fundamentals. While the “Great Rotation” could clearly impact market levels in the short-term, companies are not intrinsically more valuable simply because investors are currently willing to pay higher prices. In the long-run, the market will price stocks relative to intrinsic value – the discounted cash flows that investors can extract from businesses over the years and decades to come.

In the short-term, the relationship between price and value can stretch. Even if prices exceed intrinsic value, further increases are possible (see the Tech Bubble of the late 1990’s).

While we cannot predict short-term market movements, this is not an impediment to our true goal: making intelligent long-term investment decisions.