CONSERVE. PLAN. GROW.®

At the 2016 Berkshire Hathaway shareholder meeting, Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger were asked about the impact of negative interest rates when valuing a business. Warren’s answer touched on the peculiarity of the current environment and how it impacts decision-making at Berkshire Hathaway. Charlie, who’s known for his one-liners, said the following:

“If you’re not confused then you haven’t thought about it correctly.”

(Warren’s reply: “I’ve thought about it correctly then.”)

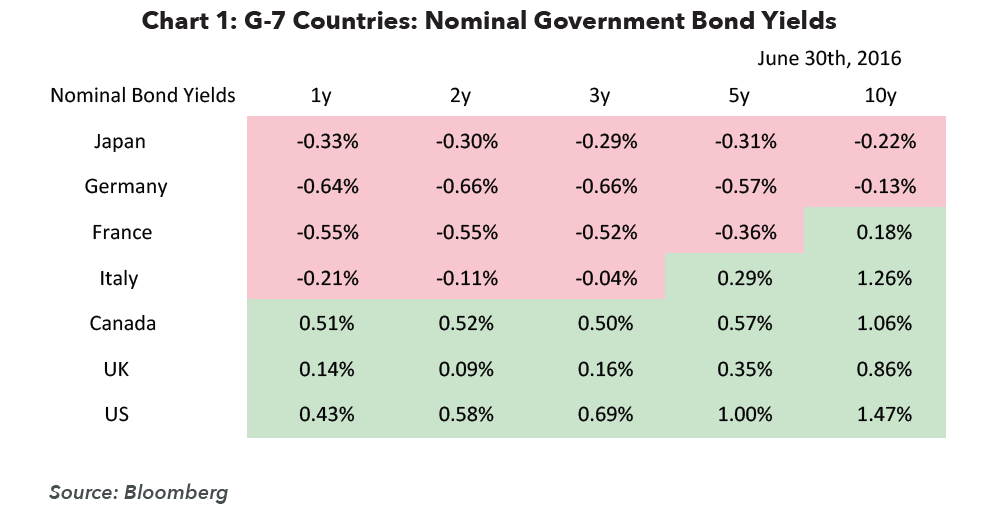

The basic math of investing was captured by the Greek story teller Aesop in 600 BC – “A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.” Now consider the current state of affairs in Germany: as we go to press, the yield on a 10-year German government bund is negative. An investor buying €10,000 of these bunds will receive less than €10,000 back, in total, from now through 2026. That sounds like a pretty bad deal to us. Strangely, this is quite common in today’s world: according to credit rating agency Fitch, there was $11.7 trillion of negative-yielding bonds in the market at the end of June (see Chart 1). The relentless decline in interest rates has been an unexpected occurrence for most investors who forecasted that extraordinary monetary support would induce inflation and drive rates higher.

Negative macro surprises have seemingly become more commonplace since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). The outcome from the Brexit vote is the latest example (“Remain” was a heavy favorite in UK betting markets). Unexpected events that shake market confidence will continue to occur every so often, as they always have. Choppy waters are simply an unavoidable part of investing (in the past decade, we’ve dealt with the Global Financial Crisis, the Greek / European debt crisis of 2011-2012, economic challenges in the BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India and China), and the broad decline of commodity prices, to name a few examples).

While Brexit currently dominates the airwaves, we try not to let unpredictable political and macroeconomic events distract us from constructing portfolios of reasonably priced, high quality companies. Even in the face of these headwinds, companies are working to innovate and create value for customers and investors. Creative destruction, fueled by profit motives, moves the world forward. It also creates enormous financial rewards for the disruptors. Unlike the next quarter point change in the fed funds rate, these developments will impact businesses for years to come.

Reinventing Mobile

Consider the example of a single product over the past decade – the smartphone.

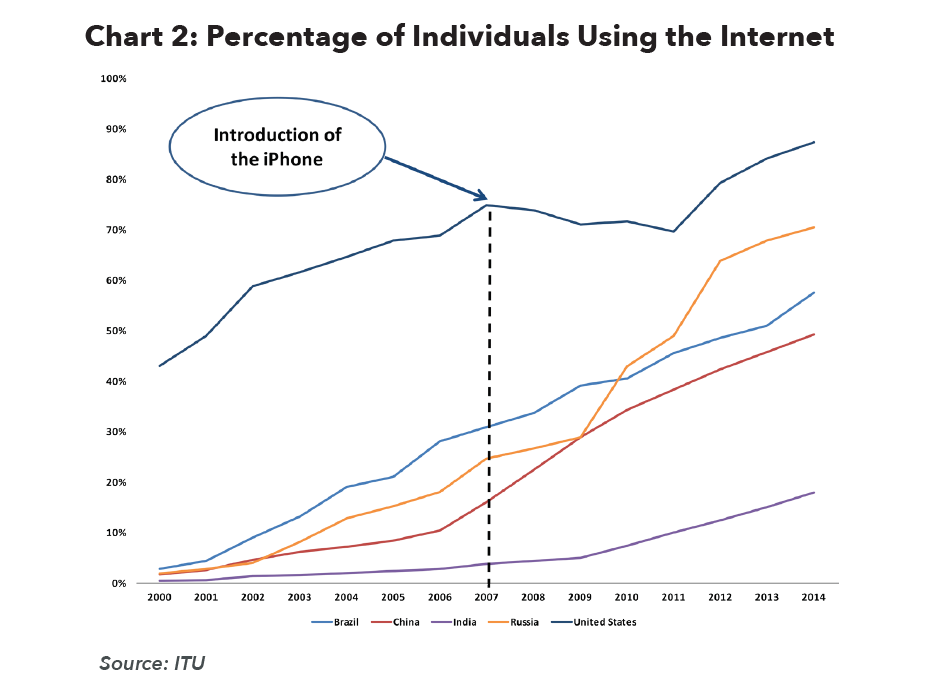

The smartphone has become the primary device for accessing the Internet for billions of people around the world, particularly in developing markets. Relentless competition has driven the average price for a smartphone down by roughly 50% over the past five years. As a result, the number of global smartphone users has quintupled since 2010, to more than 2.5 billion. Global Internet penetration is now 42%, compared to 15% a decade ago (see Chart 2). This trend should continue, with billions of incremental users expected to come online over the next decade.

Addressing New Markets

The business opportunities produced by the smartphone go well beyond selling devices. The proliferation of mobile computing has disrupted a broad range of industries and business models.

For example, mobile advertising in the United States increased from a rounding error in 2010 to a $21 billion business in 2015. It’s interesting to think about the quality of advertising opportunities on smartphones and on social networks relative to other forms of media, like newspapers. In the print edition of The New York Times, for example, advertisements are identically presented to each of the paper’s 1.1 million subscribers (circulation at year end 2015). Compare this to ads on Facebook, which are targeted to each individual user. The ability to effectively target the consumer meaningfully improves the value of the advertisement for both the advertiser and the user (marketers can reach the right audience with the right product and users see more relevant ads).

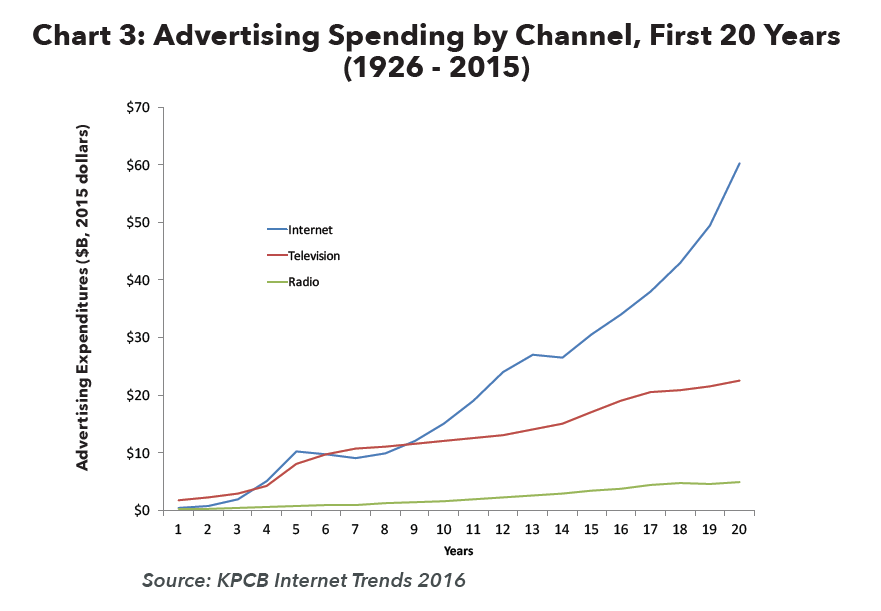

This is reflected in the numbers: after 20 years, advertising on the Internet in the U.S. (includes desktop and mobile advertising) generates $60 billion in annual revenues. Adjusted for inflation, this is three times larger than the television advertising market after its first 20 years – and more than 10 times larger than the radio advertising market after its first two decades (see Chart 3).

Facebook, a dominant player in the online advertising market, was founded in 2004. At the time of the company’s IPO in May 2012, Facebook had less than $500 million in annual mobile advertising revenues. Last year – just three years later – Facebook reported $13 billion in mobile advertising revenues (The New York Times, by comparison, reported $640 million in ad revenues in 2015). The company’s rapid growth has been driven by its ability to capitalize on structural change in the market; its growth has not been impeded by any of the unexpected macro shocks discussed earlier.

Facebook, which was started by a college student in his dorm room 12 years ago, has a market cap of $325 billion and is the eighth most valuable public company in the United States. The company’s success – most notably its rapid ascent to immense scale in a few short years – would not have been possible without the global proliferation of smartphones over the past decade.

The Only Constant Is Change

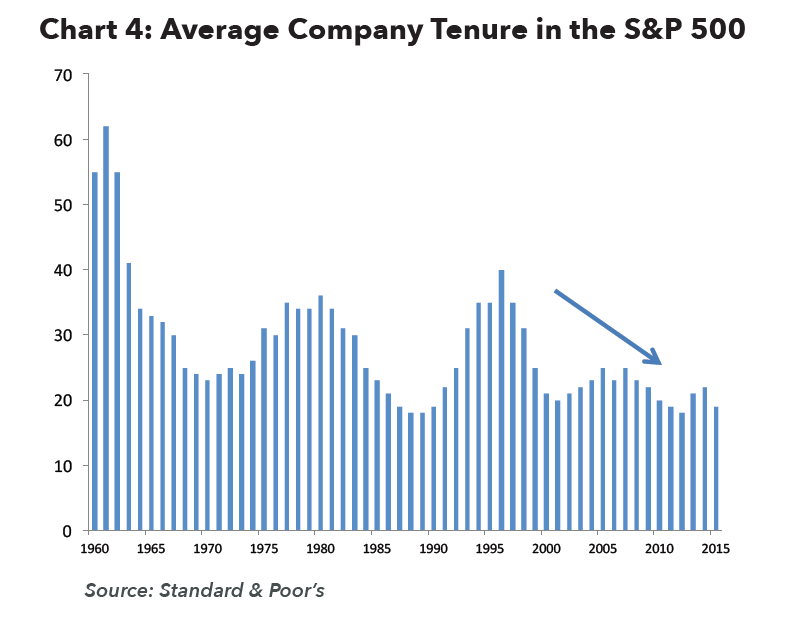

To be clear, our Facebook example is not an individual company endorsement, but rather a bellwether for the accelerating pace of change in today’s world. Over the past 20 years, the average tenure of a company in the S&P 500 Index has consistently declined (see Chart 4). As the Chart shows, the average duration for a company in the Index has fallen from 40 years to less than 20 years. While this partially reflects a changing environment (record merger & acquisition levels and the growth of private equity firms), it also points to the disruption caused by technology and the shortened period of time required to scale a business (it took Walmart 25 years to cross $10 billion in annual sales; Amazon did it in 11 years). There are few industries that have emerged unscathed as the combination of processing power, access to the Internet, and mobility has significantly transformed the business landscape.

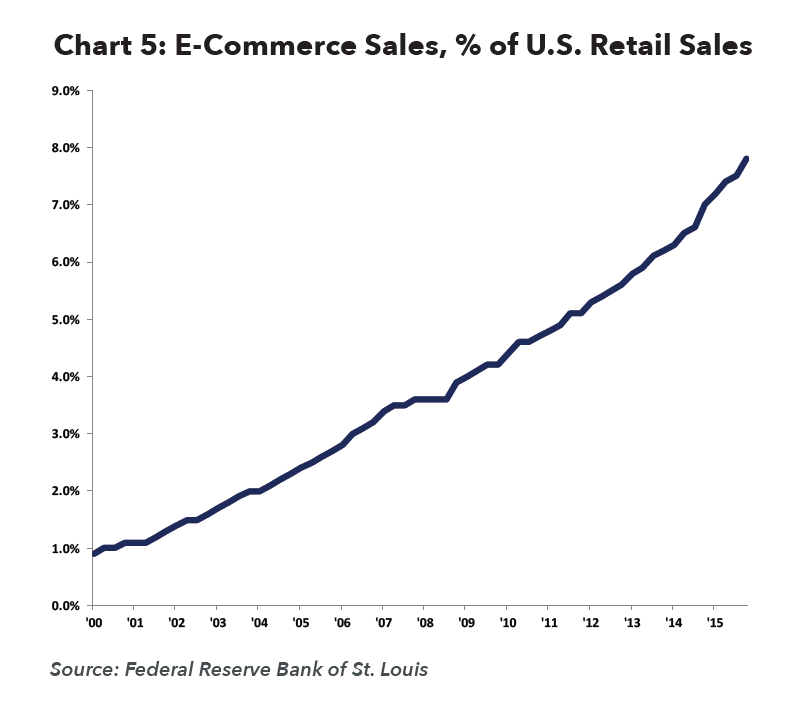

For incumbents, rapid change can be painful. In retail alone, there are dozens of former high flyers that have filed for bankruptcy (Circuit City, Radio Shack, and Borders) or faced a near-death experience (Office Max, Sears, and J.C. Penney) in the past decade. E-commerce, which is dominated in the U.S. by Amazon, continues to take share from traditional brick-and-mortar retailers (see Chart 5). This secular trend has been forceful and has not been slowed by any of the unexpected political or macroeconomic developments of the past 15 years.

To be clear, incumbents are not facing inevitable decline. They must adapt to serve customers when and where they want to do business. In retail, this means developing omnichannel capabilities and building better customer facing technology. There are a handful of legacy competitors with the financial resources and long-term focus necessary to compete in a changing world. Companies hanging on to the status quo, on the other hand, will struggle to remain relevant. To paraphrase Ernest Hemingway, they’ll become obsolete in two ways: gradually, then suddenly.

Conclusion

As investors, we benefit when we can foresee and handicap change. This requires an understanding of the key drivers of long-term competitive advantages and value creation. While macroeconomic challenges are ever present, capital will continue to fund and be allocated towards productive uses. Even in a low growth world, great businesses will still find a way to create value for investors.

From an investment perspective, volatility and short-term negativity create opportunities. During periods of market dislocation, we must attempt to keep a steadfast focus on identifying great businesses with sustainable competitive advantages that are either driving structural change or successfully mitigating emerging threats. As always, we must be cognizant of the price we’re being asked to pay by the market for these businesses relative to their underlying intrinsic value. If you pay too much money, even the best business can be a poor long-term investment.

We want to own forward-looking companies at reasonable valuations. This will not eliminate the choppiness in the market – but in the long run, it will help us safely make it to the other side.